Hey there! 👋

So you’ve probably heard about Circuit Breakers in software engineering, and if you’re like me, you might have thought: “Wait, like the ones in my house that trip when I use the microwave and hairdryer at the same time?”

Well, kind of! But instead of protecting your house from electrical overload, we’re protecting your application from service failures. Let me walk you through a simple Circuit Breaker I built and why it’s actually pretty cool.

What’s a Circuit Breaker Anyway?

Imagine you’re calling an API that’s having a bad day. Maybe the database is down, or the service is overloaded, or someone accidentally unplugged the server (it happens more than you’d think).

Without a Circuit Breaker, your app would keep hammering that broken service, wasting resources, and probably making things worse. It’s like repeatedly knocking on a door when you know nobody’s home - you’re just annoying the neighbors (or in this case, your server).

A Circuit Breaker is like a smart bouncer. It watches the service, and if it sees too many failures, it says “Nope, not today!” and stops sending requests for a while. Then it periodically checks if the service has recovered. Pretty neat, right?

The Three States of a Circuit Breaker

Our Circuit Breaker has three states, and they’re exactly what they sound like:

🔵 CLOSED (Everything’s Fine!)

This is the happy state. The circuit is closed, which means current (requests) can flow through. Your service calls go through normally, and the Circuit Breaker is just quietly counting failures in the background.

Think of it like a normal day - you’re making calls, everything works, life is good.

🔴 OPEN (Nope, Not Happening!)

When too many failures happen within a time window, the circuit “opens” (yes, the naming is a bit counterintuitive, but roll with it). In this state, the Circuit Breaker immediately returns a fallback value without even trying to call the service.

It’s like when your friend keeps canceling plans - after the third time, you stop asking and just assume they’re busy. You have a backup plan (fallback) ready.

🟡 HALF_OPEN (Testing the Waters)

After the circuit has been open for a while, it enters the “half-open” state. This is like cautiously poking the service with a stick to see if it’s alive. If the test call succeeds, great! Back to CLOSED. If it fails, back to OPEN we go.

It’s like checking if your friend is actually home before knocking - you send a text first.

How My Implementation Works

Let me break down the key parts of my Circuit Breaker:

The Configuration

The configuration uses Spring Boot’s @ConfigurationProperties to load values from application.yml:

@Component

@ConfigurationProperties(prefix = "app.circuitbreaker")

public class AppConfig {

private int failureThreshold = 5;

private long rollingWindowMillis = 10000;

private long slidingWindowSize = 5000;

}

And in application.yml:

app:

circuitbreaker:

failureThreshold: 5

rollingWindowMillis: 10000

slidingWindowSize: 5000

So the configuration is:

- 5 failures within 10 seconds (rollingWindowMillis) = circuit opens

- Stays open for 5 seconds (slidingWindowSize) before trying half-open

- Then makes a test call to see if the service has recovered

The Main Logic

The heart of the Circuit Breaker is the execute method:

public <T> T execute(Supplier<T> call, Supplier<T> fallback)

You give it:

call: The actual service call you want to makefallback: What to return if things go wrong

And it handles all the state management for you. Pretty clean, right?

State Transitions in Action

CLOSED → OPEN: When a call fails in CLOSED state, we record the failure timestamp. If we hit the failure threshold within the rolling window, boom - circuit opens!

private void recordFailure(long timestamp) {

failureTimestamps.addLast(timestamp);

pruneOldFailures(timestamp); // Clean up old failures

if (failureTimestamps.size() >= failureThreshold) {

transitionToOpen(timestamp);

}

}

OPEN → HALF_OPEN: After the timeout period, the next request will transition to HALF_OPEN:

if (state == State.OPEN) {

if (now < openUntil.get()) {

return fallback.get(); // Still too early, use fallback

} else {

// Time's up! Let's try half-open

state = State.HALF_OPEN;

}

}

HALF_OPEN → CLOSED or OPEN: In half-open, we make ONE test call. If it succeeds, we reset everything and go back to CLOSED. If it fails, back to OPEN we go.

if (state == State.HALF_OPEN) {

if (!halfOpenTrialInProgress.compareAndSet(false, true)) {

return fallback.get(); // Another thread is already testing

}

try {

T result = call.get(); // The test call

reset();

state = State.CLOSED; // Success! Back to normal

return result;

} catch (Throwable ex) {

transitionToOpen(now); // Failed again, stay open

return fallback.get();

}

}

Thread Safety (The Boring But Important Part)

Since multiple threads might be calling this at the same time, we need to be careful. The implementation uses:

ReentrantLockfor state transitions (only one thread can change state at a time)AtomicBooleanfor the half-open trial flag (ensures only one test call happens)AtomicLongfor the open-until timestampConcurrentLinkedDequefor the failure timestamps (thread-safe queue)

It’s like having a bouncer who can handle multiple people trying to get in at once - organized chaos!

The Rolling Window Magic

One cool thing is the “rolling window” for failures. We don’t just count failures forever - we only care about recent ones. Old failures get pruned:

private void pruneOldFailures(long now) {

long cutoff = now - rollingWindowMillis;

while (true) {

Long t = failureTimestamps.peekFirst();

if (t == null || t >= cutoff) break;

failureTimestamps.pollFirst(); // Remove old failures

}

}

So if you had 5 failures at 9:00 AM, but it’s now 9:15 AM and your window is 10 seconds, those failures don’t count anymore. It’s like a service getting a fresh start!

A Quick Demo

Here’s how you’d use it:

// An unreliable service that fails 75% of the time

Supplier<String> unreliableCall = () -> {

int n = counter.incrementAndGet();

if (n % 4 != 0) {

throw new RuntimeException("remote failure " + n);

}

return "remote-success-" + n;

};

// A simple fallback

Supplier<String> fallback = () -> "cached-value";

// Use the Circuit Breaker

String result = circuitBreaker.execute(unreliableCall, fallback);

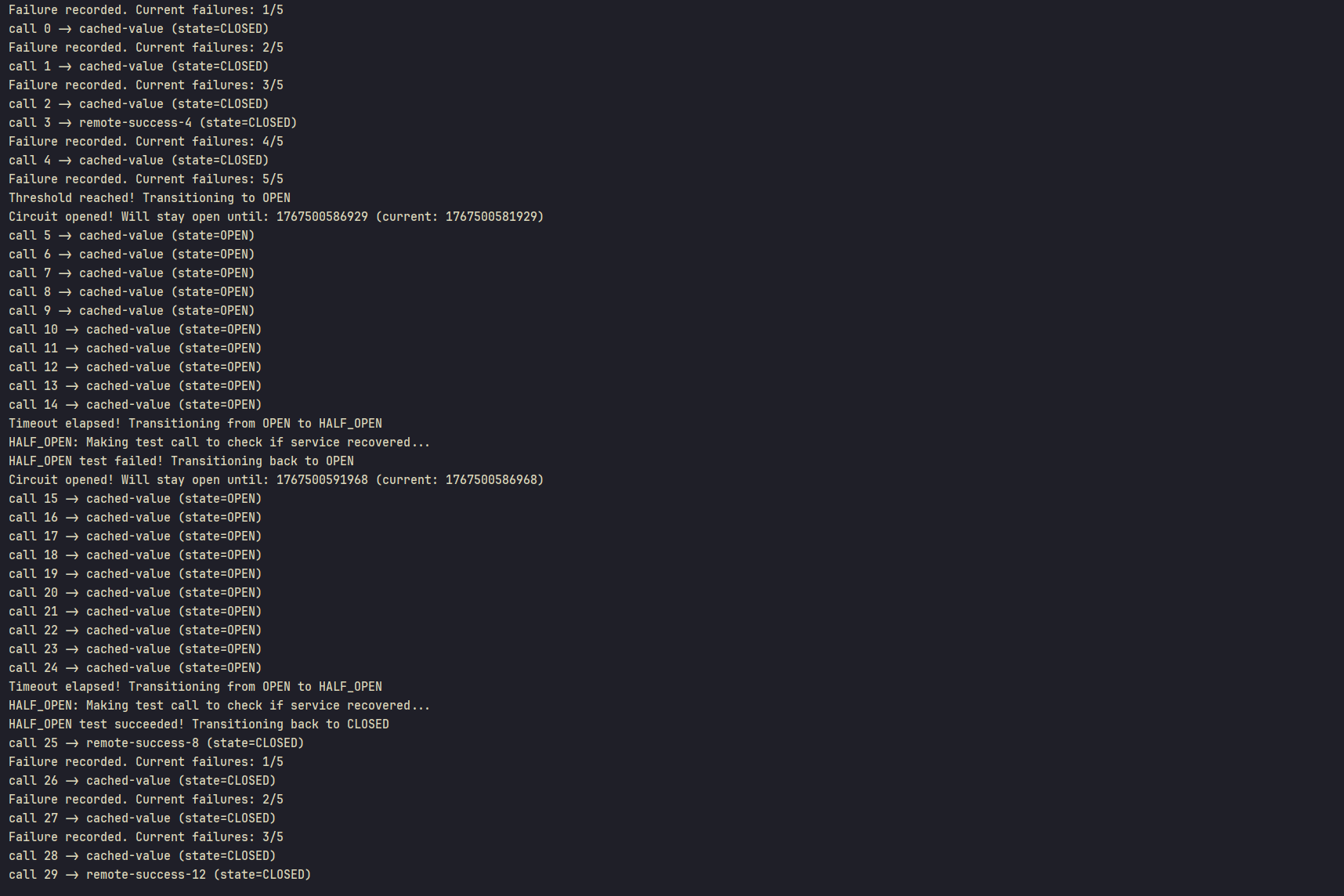

Output

What happens:

- First few calls fail → failures are recorded (you’ll see “Failure recorded. Current failures: 1/5, 2/5, 3/5…”)

- After 5 failures → circuit opens (you’ll see “Threshold reached! Transitioning to OPEN”)

- Next calls → immediately return “cached-value” (no actual call made, state stays OPEN)

- After 5 seconds → circuit goes half-open (you’ll see “Timeout elapsed! Transitioning from OPEN to HALF_OPEN”)

- Test call is made → “HALF_OPEN: Making test call to check if service recovered…”

- If test succeeds → “HALF_OPEN test succeeded! Transitioning back to CLOSED” - normal operation resumes

- If test fails → “HALF_OPEN test failed! Transitioning back to OPEN” - wait another 5 seconds before trying again

Why This Matters

Circuit Breakers are everywhere in modern distributed systems:

- Resilience: Your app doesn’t crash when external services fail

- Performance: You don’t waste time waiting for timeouts

- Resource Management: You don’t overwhelm a struggling service

- User Experience: Users get fallback responses instead of long waits

It’s like having a smart assistant who knows when to stop trying and use Plan B.

The Takeaway

Building a Circuit Breaker might seem complex, but at its core, it’s just:

- Count failures

- If too many → stop trying for a bit

- Check back later to see if things are better

- Repeat

The implementation I showed handles all the edge cases (thread safety, timing, state transitions) so you don’t have to. And that’s the beauty of good abstractions - they hide complexity and make your life easier.

So next time you’re building a service that calls other services, remember: Circuit Breakers are your friend. They’re like that friend who tells you “maybe don’t text your ex at 2 AM” - they prevent you from making bad decisions.

Happy coding! 🚀

Source Code

P.S. - In production, you might want to use battle-tested libraries like Resilience4j or Hystrix instead of rolling your own. But building one yourself is a great way to understand how they work!